prope thermās erat templum, ā fabrīs Rōmānīs aedificātum. rēx

Cogidubnus cum multīs prīncipibus servīsque prō templō

sedēbat. Quīntus prope sellam rēgis stābat. rēgem prīncipēsque

manus armātōrum custōdiēbat. prō templō erat āra ingēns, quam

omnēs aspiciēbant. Memor, togam praetextam gerēns, prope āram 5

stābat.

duo sacerdōtēs, agnam nigram dūcentēs, ad āram lentē

prōcessērunt. postquam rēx signum dedit, ūnus sacerdōs agnam

sacrificāvit. deinde Memor, quī iam tremēbat sūdābatque, alterī

sacerdōtī,10

“iubeō tē,” inquit, “ōmina īnspicere. dīc mihi: quid vidēs?”

sacerdōs, postquam iecur agnae īnspexit, anxius,

“iecur est līvidum,” inquit. “nōnne hoc mortem significat?

nōnne mortem virī clārī significat?”

Memor, quī perterritus pallēscēbat, sacerdōtī respondit,15

“minimē. dea Sūlis, quae precēs aegrōtōrum audīre solet, nōbīs

ōmina optima mīsit.”

haec verba locūtus, ad Cogidubnum sē vertit et clāmāvit,

“ōmina sunt optima! ōmina tibi remedium mīrābile significant,

quod dea Sūlis Minerva tibi favet.”20

tum rēgem ac prīncipēs Memor in apodytērium dūxit.

| manus armātōrum | a band of soldiers | iecur | liver |

| aspiciēbant: | | līvidum: līvidus | lead-colored |

| aspicere | look towards | significat: |

| praetextam: | | significāre | mean, indicate |

| praetextus | with a purple border | pallēscēbat: |

| agnam: agna | lamb | pallēscere | grow pale |

| ōmina: ōmen | omen | ac | and |

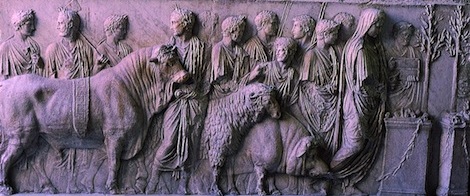

The altar at Bath. The base and the sculptured corner blocks are original; the rest of the Roman stone must have been re-used elsewhere during the Middle Ages.

At the top left of the photograph can be seen the stone statue base which is inscribed with Memor’s name.

II

deinde omnēs in eam partem thermārum intrāvērunt, ubi balneum

maximum erat. Quīntus, prīncipēs secūtus, circumspectāvit et

attonitus,

“hae thermae,” inquit, “maiōrēs sunt quam thermae

Pompēiānae!”5

servī magnā cum difficultāte Cogidubnum in balneum

dēmittere coepērunt. maximus clāmor erat. rēx prīncipibus

mandāta dabat. prīncipēs lībertōs suōs vituperābant, lībertī servōs.

tandem rēx, ē balneō ēgressus, vestīmenta, quae servī tulerant,

induit. tum omnēs fontī sacrō appropinquāvērunt.10

Cephalus, quī anxius tremēbat, prope fontem stābat, pōculum

ōrnātissimum tenēns.

“domine,” inquit, “pōculum aquae sacrae tibi offerō. aqua est

amāra, sed remedium potentissimum.”

| secūtus | having followed | dēmittere let | down, lower |

| difficultāte: difficultās | difficulty

| amāra: amārus | bitter |

haec verba locūtus, rēgī pōculum obtulit. rēx pōculum ad labra 15

sustulit.

subitō Quīntus, pōculum cōnspicātus, manum rēgis prēnsāvit

et clāmāvit,

“nōlī bibere! hoc est pōculum venēnātum. pōculum huius modī

in urbe Alexandrīā vīdī.”20

“longē errās,” respondit rēx. “nēmō mihi nocēre vult. nēmō

umquam mortem mihi parāre temptāvit.”

“rēx summae virtūtis es,” respondit Quīntus. “sed, quamquam

nūllum perīculum timēs, tūtius est tibi vērum scīre. pōculum

īnspicere velim. dā mihi!”25

tum pōculum Quīntus īnspicere coepit. Cephalus tamen

pōculum ē manibus Quīntī rapere temptābat. maxima pars

spectātōrum stābat immōta. sed Dumnorix, prīnceps Rēgnēnsium,

saeviēbat tamquam leō furēns. pōculum rapuit et Cephalō obtulit.

“facile est nōbīs vērum cognōscere,” clāmāvit. “iubeō tē 30

pōculum haurīre. num aquam bibere timēs?”

Cephalus pōculum haurīre nōluit, et ad genua rēgis prōcubuit.

rēx immōtus stābat. cēterī prīncipēs lībertum frūstrā resistentem

prēnsāvērunt. Cephalus, ā prīncipibus coāctus, venēnum hausit.

deinde, vehementer tremēns, gemitum ingentem dedit et mortuus 35

prōcubuit.

| labra: labrum | lip | genua: genū | knee |

| prēnsāvit: prēnsāre | take hold of, clutch

| coāctus: cōgere | force, compel |

About the Language I: More About Participles

AIn Stage 20 you met the present participle:

lībertus dominum intrantem vīdit.

The freedman saw his master entering.

BIn Stage 21 you met the perfect passive participle:

fabrī, ab architectō laudātī, dīligenter labōrābant.

The craftsmen, (having been) praised by the architect, were working hard.

CIn Stage 22 you met the perfect active participle:

Vilbia, thermās ingressa, clāmōrem audīvit.

Vilbia, having entered the baths, heard a noise.

DTranslate the following examples:

1rēx, in mediā turbā sedēns, prīncipēs salūtāvit.

2lībertus, in cubiculum regressus, Memorem excitāre temptāvit.

3Vilbia fībulam, ā Modestō datam, Rubriae ostendit.

4sacerdōtēs, deam precātī, agnam sacrificāvērunt.

5templum, ā Rōmānīs aedificātum, prope fontem sacrum erat.

6sorōrēs, in tabernā labōrantēs, mīlitem cōnspexērunt.

7fūr rēs, in fontem iniectās, quaesīvit.

8nōnnūllae ancillae, ā dominā incitātae, cubiculum parāvērunt.

Pick out the noun and participle pair in each sentence and state whether the participle is present, perfect passive, or perfect active.

EGive the case, number, and gender of each noun and participle pair in Section D.

epistula Cephalī

postquam Cephalus periit, servus eius rēgī epistulam trādidit, ā

Cephalō ipsō scrīptam:

“rēx Cogidubne, in maximō perīculō es. Memor īnsānit. mortem

tuam cupit. iussit mē rem efficere. invītus Memorī pāruī. fortasse

mihi nōn crēdis. sed tōtam rem tibi nārrāre velim.5

“ubi tū ad hās thermās advēnistī, remedium quaerēns, Memor

mē ad vīllam suam quam celerrimē arcessīvit. vīllam ingressus,

Memorem perterritum invēnī. attonitus eram. numquam

Memorem adeō perterritum vīderam. Memor mihi,

“‘Imperātor mortem Cogidubnī cupit,’ inquit. ‘iubeō tē hanc 10

rem administrāre. iubeō tē venēnum parāre. tibi necesse est eum

interficere. Cogidubnus enim est homō ingeniī prāvī.’

“Memorī respondī,

“‘longē errās. Cogidubnus est vir ingeniī optimī. tālem rem

facere nōlō.’15

“Memor īrātus,

“‘sceleste!’ inquit, ‘lībertus meus es, et servus meus erās. tē

līberāvī et tibi multam pecūniam dedī. mandāta mea facere dēbēs.

cūr mihi obstās?’

“rēx Cogidubne, diū recūsāvī obstinātus. diū beneficia tua 20

commemorāvī. Memor tamen custōdem arcessīvit, quī mē

verberāvit. ā custōde paene interfectus, Memorī tandem cessī.

“ad casam meam regressus, venēnum invītus parāvī. scrīpsī

tamen hanc epistulam et servō fidēlī trādidī. iussī servum tibi

epistulam trādere. veniam petō, quamquam facinus scelestum 25

parāvī. Memor nocēns est. Memor coēgit mē hanc rem efficere.

Memorem, nōn mē, pūnīre dēbēs.”

| īnsānit: īnsānīre | be crazy, be insane |

| beneficia: beneficium | act of kindness, favor |

| facinus: facinus | crime |

| coēgit: cōgere | force, compel |

About the Language II: Comparison of Adverbs

AStudy the following sentences:

1Loquāx vōcem suāvem habet; suāviter cantāre potest.

Loquax has a sweet voice; he can sing sweetly.

2Melissa vōcem suāviōrem habet; suāvius cantāre potest.

Melissa has a sweeter voice; she can sing more sweetly.

3Helena vōcem suāvissimam habet; suāvissimē cantāre potest.

Helena has a very sweet voice; she can sing very sweetly.

The words in boldface above are adverbs. An adverb describes a verb, adjective, or other adverb.

Study the following patterns:

| Comparative |

| adjective: | suāvior, suāvior, suāvius | adverb: | suāvius |

| tardior, tardior, tardius | tardius |

| celerior, celerior, celerius | celerius |

| Superlative |

| adjective: | suāvissimus | adverb: | suāvissimē |

| tardissimus | tardissimē |

| celerrimus | celerrimē |

BStudy the following sentences:

1balneum Pompēiānum erat magnum; Quīntum magnopere dēlectāvit.

The bath at Pompeii was large; it pleased Quintus a lot.

2balneum Alexandrīnum erat maius; Quīntum magis dēlectāvit.

The bath at Alexandria was larger; it pleased Quintus more.

3balneum Britannicum erat maximum; Quīntum maximē dēlectāvit.

The bath in Britain was the largest; it pleased Quintus the most.

Some adverbs, like their corresponding adjectives, are compared irregularly.

| positive | comparative | superlative |

| bene | melius | optimē |

| well | better | best, very well |

| male | peius | pessimē |

| badly | worse worst, | very badly |

| magnopere | magis | maximē |

| greatly | more | most, very greatly |

| paulum | minus | minimē |

| little | less | least, very little |

| multum | plūs | plūrimum |

| much | more | most, very much |

For the adjectives corresponding to these adverbs, see page 301 in the Language Information.

CNotice a special meaning for the comparative:

medicus tardius advēnit.

The doctor arrived too late (i.e. later than necessary).

DNotice the idiomatic use of the superlative with quam:

medicus quam celerrimē advēnit.

The doctor arrived as quickly as possible.

ETranslate the following examples:

1āthlēta Cantiacus celerius quam cēterī cucurrit.

2fūrēs senem facillimē superāvērunt.

3ubi hoc audīvī, magis timēbam.

4mīlitēs, quam fortissimē pugnāte!

5medicus tē melius quam astrologus sānāre potest.

6illī iuvenēs fīliam nostram avidius spectant.

7canis dominum mortuum fidēliter custōdiēbat.

8eī, quī male vīxērunt, male pereunt.

Britannia perdomita

When you have read this story, answer the questions at the end.

Salvius cum Memore anxius colloquium habet. servus ingressus ad

Memorem currit.

servus:domine, rēx Cogidubnus hūc venit. rēx togam

praetextam ōrnāmentaque gerit. magnum

numerum armātōrum sēcum dūcit.5

Memor:rēx armātōs hūc dūcit? togam praetextam gerit?

Salvius:Cogidubnus, nōs suspicātus, ultiōnem petit.

Memor, tibi necesse est mē adiuvāre. nōs enim

Rōmānī sumus, Cogidubnus barbarus.

intrat Cogidubnus. in manibus epistulam tenet, ā Cephalō scrīptam.10

Cogidubnus:Memor, tū illās īnsidiās parāvistī. tū iussistī

Cephalum venēnum comparāre et mē necāre. sed

Cephalus, lībertus tuus, mihi omnia patefēcit.

Memor:Cogidubne, id quod dīcis, absurdum est. mortuus

est Cephalus.15

Cogidubnus:Cephalus homō magnae prūdentiae erat. tibi nōn

crēdidit. invītus tibi pāruit. simulac mandāta ista

dedistī, scrīpsit Cephalus epistulam in quā omnia

patefēcit. servus, ā Cephalō missus, epistulam mihi

tulit.20

Memor:epistula falsa est, servus mendācissimus.

Cogidubnus:tū, nōn servus, es mendāx. servus enim, multa

tormenta passus, in eādem sententiā mānsit.

Salvius:Cogidubne, cūr armātōs hūc dūxistī?

Cogidubnus:Memorem ē cūrā thermārum iam dēmōvī.25

Memor:quid dīcis? tū mē dēmōvistī? ego innocēns sum.

Salv …

| perdomita: perdomitus | conquered |

| armātōrum: armātī | armed men |

| suspicātus | having suspected |

| ultiōnem: ultiō | revenge |

| patefēcit: patefacere | reveal |

| absurdum: absurdus | absurd |

| falsa: falsus | false, untrue |

| tormenta: tormentum | torture |

| passus | having suffered |

| eādem: īdem | the same |

| dēmōvī: dēmovēre | dismiss |

Salvius:rēx Cogidubne, quid fēcistī? tū, quī barbarus es,

haruspicem Rōmānum dēmovēre audēs? nimium

audēs! tū, summōs honōrēs ā nōbīs adeptus,30

numquam contentus fuistī. nōs diū vexāvistī. nunc

dēnique, cum armātīs hūc ingressus, perfidiam

apertē ostendis. Imperātor Domitiānus,

arrogantiam tuam diū passus, ad mē epistulam

nūper mīsit. in hāc epistulā iussit mē rēgnum tuum 35

occupāre. iubeō tē igitur ad aulam statim redīre.

Cogidubnus:ēn iūstitia Rōmāna! ēn fidēs! nūllī perfidiōrēs sunt

quam Rōmānī. stultissimus fuī, quod Rōmānīs

adhūc crēdidī. amīcōs meōs prōdidī; rēgnum

meum āmīsī. ōlim, ā Rōmānīs dēceptus, ōrnāmenta 40

honōrēsque Rōmānōs accēpī. hodiē ista

ōrnāmenta, mihi ā Rōmānīs data, humī iaciō. Salvī,

mitte nūntium ad istum Imperātōrem, “nōs

Cogidubnum tandem vīcimus. Britannia

perdomita est.”45

senex, haec locūtus, lentē per iānuam exit.

| perfidiam: | | fidēs | loyalty, |

| perfidia | treachery | | trustworthiness |

| apertē | openly | perfidiōrēs: perfidus | treacherous, |

| rēgnum: rēgnum | kingdom | perfidus | untrustworthy |

| occupāre | seize, take over | adhūc | until now |

| ēn iūstitia! | so this is justice! | prōdidī: prōdere | betray |

| | vīcimus: vincere | conquer |

Questions

1Who is described as anxius?

2From the slave’s words (lines 3–5), how do Memor and Salvius know that Cogidubnus’ visit is not an ordinary one (two reasons)?

3What is Salvius’ explanation for Cogidubnus’ visit (line 7)?

4Why does he think Memor should help him?

5What accusation does Cogidubnus make against Memor (lines 11–12)?

6Why is Memor certain that Cogidubnus is unable to prove his accusation (lines 14–15)?

7What proof does Cogidubnus have? How did it come into his possession (lines 17–20)?

8Why is Cogidubnus convinced that the slave is trustworthy?

9What question does Salvius ask Cogidubnus?

10Why do you think that he has remained silent up to this point?

11What answer does Cogidubnus give to Salvius’ question?

12Why does Salvius interrupt Memor’s response to that answer?

13Salvius tells Cogidubnus: nimium audēs (lines 29–30). How has he explained that comment in the words he says immediately before it?

14What two other accusations does he make?

15What order does Salvius say he has received? Who has sent it (lines 33–36)?

16ista ōrnāmenta … humī iaciō (lines 41–42). What is Cogidubnus doing when he says these words? Why do you think he does this?

17How are the attitudes or situations of Memor, Salvius, and Cogidubnus different at the end of this story from what they were at the beginning? Make one point about each character.

Word Patterns: Verbs and Nouns

A Study the form and meaning of the following verbs and nouns:

| infinitive | perfect passive | noun |

| | participle |

| pingere | to paint | pictus | pictor | painter |

| vincere | to win | victus | victor | winner, victor |

| līberāre | to set free | līberātus | līberātor | liberator |

BUsing the pattern in Section A as a guide, complete the table below:

| emere | to buy | emptus | emptor | . . . . . |

| legere | . . . . . | lēctus | . . . . . | reader |

| spectāre | . . . . . | spectātus | . . . . . | . . . . . |

CWhat do the following nouns mean:

dēfēnsor, vēnditor, prōditor, amātor, praecursor, arātor, gubernātor, saltātor

DMany English nouns ending in -or are derived from Latin verbs. Which verbs do the following English nouns come from? Use the Complete Vocabulary to help you if necessary.

demonstrator, curator, navigator, narrator, tractor, doctor

ESuggest what the ending -or indicates in Latin and English.

Practicing the Language

AComplete each sentence with the correct word. Then translate.

1nōs ancillae fessae sumus; semper in vīllā (labōrāmus, labōrātis, labōrant).

2“quid faciunt illī servī?” “saxa ad plaustrum (ferimus, fertis, ferunt).”

3quamquam prope āram (stābāmus, stābātis, stābant), sacrificium vidēre nōn poterāmus.

4ubi prīncipēs fontī (appropinquābāmus, appropinquābātis, appropinquābant), Cephalus prōcessit, pōculum tenēns.

5in maximō perīculō estis, quod fīlium rēgis (interfēcimus, interfēcistis, interfēcērunt).

6nōs, quī fontem sacrum numquam (vīderāmus, vīderātis, vīderant), ad thermās cum rēge īre cupiēbāmus.

7dominī nostrī sunt benignī; nōbīs semper satis cibī (praebēmus, praebētis, praebent).

BTranslate the verbs in the left-hand column. Then, keeping the person and number unchanged, use the verb in parentheses to form a phrase with the infinitive and translate again. For example:

festīnat.(dēbeō)

He hurries.

This becomes:festīnāre dēbet.

He ought to hurry.

1incipitis.(dēbeō)

2pārēmus.(volō)

3adiuvat.(possum)

4reveniunt.(dēbeō)

5ēligimus.(possum)

6num dissentīs?(volō)

CComplete each sentence with the most suitable participle from the list below and then translate.

adeptus, locūtus, ingressus, missus, excitātus, superātus

1Cogidubnus, haec verba . . . . ., ab aulā discessit.

2nūntius, ab amīcīs meīs . . . . ., epistulam mihi trādidit.

3fūr, vīllam . . . . ., cautē circumspectāvit.

4Bulbus, ā Modestō . . . . ., sub mēnsā iacēbat.

5haruspex, ā Cephalō . . . . ., invītus ē lectō surrēxit.

6mīles, amulētum . . . . ., in fontem iniēcit.

Roman Religious Beliefs

Sacrifices and Presents to the Gods

In our stories Cogidubnus sacrificed a lamb to Sulis Minerva in the hope that the goddess would be pleased with his gift and would restore him to health. This was regarded as the right and proper thing to do in such circumstances. From earliest times the Romans had believed that all things were controlled by nūmina (spirits or divinities). The power of numina was seen, for example, in fire or in the changing of the seasons. To ensure that the numina used their power for good rather than harm, the early Romans presented them with offerings of food and wine. After the third century b.c., when Roman spirits and agricultural deities were incorporated into the Greek pantheon (system of gods), this idea of a contract between mortals and the gods persisted.

To communicate their wishes to the gods, many Romans presented an animal sacrifice, gave a gift, or accompanied their prayers with promises of offerings if the favors were granted. These promises were known as vōta. In this way, they thought, they could keep on good terms with the gods and stand a better chance of having their prayers answered. This was true at all levels of society. For example, if a general was going off to war, there would be a solemn public ceremony at which prayers and expensive sacrifices would be offered to the gods. Ordinary citizens would also offer sacrifices, hoping for a successful business deal, a safe voyage, or the birth of a child; and in many Roman homes, to ensure the family’s prosperity, offerings of food would be made to Vesta, the spirit of the hearth, and to the larēs and penātēs, the spirits of the household and food cupboard.

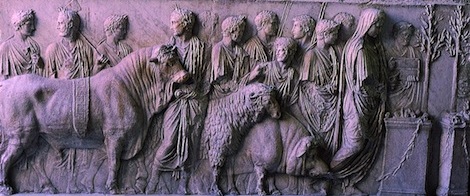

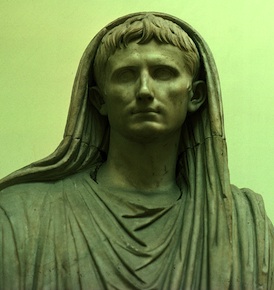

An emperor, as Chief Priest, leads a solemn procession. He covers his head with a fold of his toga. A bull, a sheep, and a pig are to be sacrificed.

People also offered sacrifices and presents to the gods to honor them at their festivals, to thank them for some success or an escape from danger, or to keep a promise. For example, a cavalry officer stationed in the north of England set up an altar to the god Silvanus with this inscription:

C. Tetius Veturius Micianus, captain of the Sebosian cavalry squadron, set this up as he promised to Silvanus the unconquered, in thanks for capturing a beautiful boar, which many people before him tried to do but failed.

Another inscription from a grateful woman in north Italy reads:

Tullia Superiana takes pleasure in keeping her promise to Minerva the unforgetting for giving her her hair back.

Often people promised to give something to the gods if they answered their prayers. Thus, Censorinus dedicated this thin silver plaque to Mars-Alator, in order to fulfill a vow.

A model liver. Significant areas are labeled to help haruspices interpret any markings.

Divination

An haruspex, like Memor, would be present at important sacrifices. He and his assistants would watch the way in which the victim fell; they would observe the smoke and flames when parts of the victim were placed on the altar fire; and, above all, they would cut the victim open and examine its entrails, especially the liver. They would look for anything unusual about the liver’s size or shape, observe its color and texture, and note whether it had spots on its surface. They would then interpret what they saw and announce to the sacrificer whether the ōmina from the gods were favorable or not.

Such attempts to discover the future were known as divination. Another type of divination was performed by priests known as augurēs (augurs), who based their predictions on observations of the flight of birds. They would note the direction of flight and observe whether the birds flew together or separately, what kind of birds they were, and what noises they made.

The Roman State Religion

Religion in Rome and Italy included a bewildering variety of gods, demigods, spirits, rituals and ceremonies, whose origin and meaning was often a mystery to the worshipers themselves. The Roman state respected this variety but particularly promoted the worship of Jupiter and his family of gods and goddesses, especially Juno, Minerva, Ceres, Apollo, Diana, Mars, and Venus. They were closely linked with their equivalent Greek deities, whose characteristics and colorful mythology were readily taken over by the Romans.

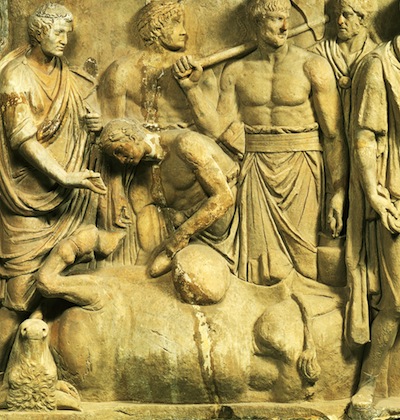

In this sculpture of a sacrifice, notice the pipe-player, and the attendants with the decorated victim.

A priest’s ritual headdress, from Roman Britain.

The rituals and ceremonies were organized by colleges of priests and other religious officials, many of whom were senators, and the festivals and sacrifices were carried out by them on behalf of the state. Salvius, for example, was a member of the Arval Brotherhood, whose religious duties included praying for the emperor and his family. The emperor always held the position of Pontifex Maximus or Chief Priest. Great attention was paid to the details of worship. Everyone who watched the ceremonies had to stand quite still and silent, like Plancus in Stage 17. Every word had to be pronounced correctly; otherwise the whole ceremony had to be restarted. A pipe-player was employed to drown out noises and cries, which were thought to be unlucky for the ritual.

Three sculptures from Bath illustrate the mixture of British and Roman religion there.

Above: a gilded bronze head of Sulis Minerva, presumably from her statue in the temple, shows the goddess as the Romans pictured her.

Top right: three Celtic mother-goddesses.

Right: Nemetona and the horned Loucetius Mars.

Religion and Romanization

The Roman state religion played an important part in the Romanization of the provinces of the empire. The Romans generally tolerated the religious beliefs and practices of their subject peoples unless they were thought to threaten their rule or their relationship with the gods, which was so carefully fostered by sacrifices and correct rituals. They encouraged their subjects to identify their own gods with Roman gods who shared some of the same characteristics. We have seen at Aquae Sulis how the Celtic Sulis and the Roman Minerva were merged into one goddess, Sulis Minerva, and how a temple in the Roman style was built in her honor.

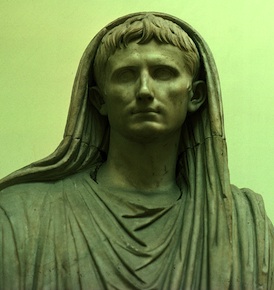

Emperor Augustus as Pontifex Maximus.

Another feature of Roman religion which was intended to encourage acceptance of Roman rule was the worship of the emperor. In Rome itself, emperor worship was generally dis-couraged, while the emperor was alive. However, the peoples of the eastern provinces of the Roman empire had always regarded their kings and rulers as divine and were equally ready to pay divine honors to the Roman emperors. Gradually the Romans introduced this idea in the west as well. The Britons and other western peoples were encouraged to worship the genius (protecting spirit) of the emperor, linked with the goddess Roma. Altars were erected in honor of “Rome and the emperor.” When an emperor died, it was usual to deify him (make him a god), and temples were often built to honor the deified emperor. One such temple, that of Claudius in Camulodunum (Colchester), was destroyed, before it was even finished, during the revolt led by Queen Boudica in a.d. 60. The historian Tacitus tells us that this temple was a blatant stronghold of alien rule, and its observances were a pretext to make the natives appointed as its priests drain the whole country dry.

In general, however, the policy of promoting Roman religion and emperor worship proved successful in the provinces. Like other forms of Romanization it became popular with the upper and middle classes, who looked to Rome to promote their careers; it helped to make Roman rule acceptable, reduced the chance of uprisings, and gave many people in the provinces a sense that they belonged to one great empire.

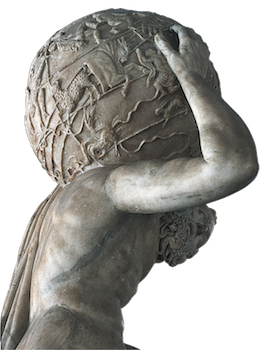

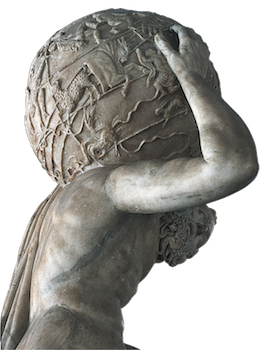

Atlas holding the globe inscribed with constellations.

Astrology

Many Romans were content with the official state religion but some found greater satisfaction in other forms of belief. Many took part in both the state religion and some other kind of worship without feeling any conflict between the two. One very popular form of belief was astrology. Astrologers, like the one in Barbillus’ household in Unit 2, claimed that the events in a person’s life were controlled by the stars and that it was possible to forecast the future by studying the positions and movements of stars and planets. The position of the stars at the time of a person’s birth was known as an hōroscopos (horoscope) and regarded as particularly important. Astrology was officially disapproved of, especially if people used it to try to determine when their relatives or acquaintances were going to die, and from time to time all astrologers were banished from Rome. It was a particularly serious offense to inquire about the horoscope of the emperor. Several emperors, however, were themselves firm believers in astrology and, like Barbillus, kept astrologers of their own.

Word Study

AComplete the following analogies with words from the Stage 23 Vocabulary Checklist:

1venīre : īre : : ___ : resistere

2fortis : ignāvus : : ___ : benignus

3verbum : dīcere : : ___ : iubēre

4exitium : dēlēre : : ___ : parcere

5ingressus : intrāre : : ___ : dīcere

6pecūnia : numerāre : : discus : ___

7sānāre : interficere : : remedium : ___

BGive a definition for each of the following derivatives of cēdō, cēdere, cessī:

| 1precedent | 6secede |

| 2recession | 7intercession |

| 3cessation | 8incessant |

| 4antecedent | 9predecessor |

| 5necessary |

CCopy the following words. Then put parentheses around the Latin root from this Stage contained inside these derivatives; give the Latin word and its meaning from which the derivative comes.

For example: conservation con(serva)tion servāre – to save

| 1declaration | 6potentate |

| 2depraved | 7retaliate |

| 3elocution | 8science |

| 4errant | 9venial |

| 5mandate | 10regression |

Stage 23 Vocabulary Checklist

| administrō, administrāre, administrāvī | manage |

| cēdō, cēdere, cessī | give in, give way |

| clārus, clāra, clārum | famous |

| commemorō, commemorāre, |

| commemorāvī, commemorātus | mention, recall |

| cōnspicātus, cōnspicāta, cōnspicātum | having caught sight of |

| cūra, cūrae, f. | care |

| enim | for |

| errō, errāre, errāvī | make a mistake |

| gerō, gerere, gessī, gestus | wear |

| honor, honōris, m. | honor |

| iaciō, iacere, iēcī, iactus | throw |

| immōtus, immōta, immōtum | still, motionless |

| ingenium, ingeniī, n. | character |

| locūtus, locūta, locūtum | having spoken |

| magnopere | greatly |

| magis | more, rather |

| maximē | very greatly, most of all |

| mandātum, mandātī, n. | instruction, order |

| modus, modī, m. | manner, way, kind |

| rēs huius modī | a thing of this kind |

| nimium, nimiī, n. | too much |

| ōrnō, ōrnāre, ōrnāvī, ōrnātus | decorate |

| pāreō, pārēre, pāruī (+ dat) | obey |

| potēns, potēns, potēns, |

| gen. potentis | powerful |

| prāvus, prāva, prāvum | evil |

| regressus, regressa, regressum | having returned |

| scio, scīre, scīvī | know |

| tālis, tālis, tāle | such |

| tamquam | as, like |

| umquam | ever |

| venēnum, venēnī, n. | poison |

| venia, veniae, f. | mercy |

This bronze statuette represents a Romano-British worshiper bringing offerings to a god.

Linux x86_64

5.0 AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko; compatible; ClaudeBot/1.0; +claudebot@anthropic.com)