| rāta: rērī | think |

| honestior: honestus | honorable |

| incertae: incertus | questionable |

| nuncupat: nuncupāre | name |

| rēgia: rēgius | of the king |

| vindicant: vindicāre | protect |

| sacerdōs | priestess |

| custōdiam: custōdia | custody |

| prōfluentem: prōfluere | flow forward |

| iubet = Amulius iubet | |

| forte quādam dīvinitus | by a certain chance from the gods |

| Tiberis | nominative |

| effūsus = effūsus est | |

| lēnibus: lēnis | quiet |

| stagnīs: stagnum | pool |

| (īnfantēs) posse … mergī | indirect statement dependent on spem |

| quamvīs | although, however |

| languidā: languidus | still |

| mergī: mergere | drown |

| ferentibus = eīs ferentibus | |

| dēfunctī: dēfungī (+ abl) | carry out |

| alluviē: alluviēs | overflow |

| fīcus Rūminālis | Ruminal fig-tree (on the Palatine opposite the |

| Capitol; Rumina was a goddess of suckling) | |

| Rōmulārem: Rōmulāris | Romular (associated with Romulus) |

| ferunt | they say |

| expōnunt: expōnere | expose |

1What two crimes did Amulius commit?

2What part does fate play in the story?

3What happened to Rea Silvia? How did she explain the result?

4What two things did the king do to her?

5What effect did the flooding of the Tiber have on the people assigned to get rid of the infants? Where were the babies exposed?

6What view does Livy seem to take of Rea Silvia’s explanation in line 8? How does the reader gain that impression?

vastae tum in hīs locīs sōlitūdinēs erant. tenet fāma cum fluitantem

alveum, quō iam expositī erant puerī, tenuis in siccō aqua

dēstituisset, lupam sitientem ex montibus quī circā sunt ad

puerīlem vāgītum cursum flexisse; eam submissās īnfantibus adeō

mītem praebuisse mammās ut linguā lambentem puerōs magister5

rēgiī pecoris invēnerit (Faustulō fuisse nōmen ferunt); ab eō ad

stabula Larentiae uxōrī ēdūcandōs datōs. sunt quī Larentiam

vulgātō corpore “lupam” inter pastōrēs vocātam putent: inde

locum fābulae ac mīrāculō datum.

The she-wolf on a coin.

| sōlitūdinēs: sōlitūdō | wilderness | pecoris: pecus | cattle |

| tenet fāma | the story goes | stabula: stabulum | cottage, stall |

| that) | ēdūcandōs: ēdūcāre | bring up | |

| fluitantem: fluitāre | float | datōs = datōs esse | dependent on |

| alveum: alveus | basket | tenet fāma | |

| tenuis | shallow | vulgātō corpore | by acting as a |

| in siccō | on dry land | prostitute | |

| lupam: lupa | she-wolf | inde | from this, |

| sitientem: sitīre | be thirsty | accordingly | |

| puerīlem: puerīlis | of a boy | locum: locus | occasion, reason |

| vāgītum: vāgītus | crying | ||

| flexisse: flectere | turn (dependent on tenet fāma) | ||

| submissās: submittere | let down, lower | ||

| mītem: mītis | gentle | ||

| praebuisse | dependent on tenet fāma | ||

| mammās: mamma | teat | ||

| lambentem = eam lambentem: lambere lick | |||

276 Stage 48

1When the shallow water had receded, where was the basket?

2Why did the wolf happen to be nearby? What two things did she do for the babies?

3Who was Faustulus? Where did he take the babies?

ita genitī itaque ēdūcātī, cum prīmum adolēvit aetās, nec in

stabulīs nec ad pecora segnēs vēnandō peragrāre saltūs. hinc

rōbore corporibus animīsque sūmptō iam nōn ferās tantum

subsistere, sed in latrōnēs praedā onustōs impetūs facere,

pastōribusque rapta dīvidere et cum hīs crēscente in diēs grege 5

iuvenum sēria ac iocōs celebrāre.

| genitī: genitus | born |

| adolēvit aetās | they came of age |

| nec … segnēs | (though) not inactive |

| vēnandō: vēnārī | hunt |

| peragrāre | roam (historical infinitive - as are the following verbs |

| in this section. Translate as perfect tenses.) | |

| hinc | in this exercise |

| rōbore: rōbur | strength, toughness |

| nōn … tantum | not only |

| ferās: fera | wild animal |

| subsistere | encounter, face |

| onustōs: onustus | laden |

| cum hīs | with them (the shepherds) |

| crēscente: crēscere | grow |

| in diēs | day by day |

| grege: grex | troop, flock |

| sēria: sēria | business, serious things |

1When the infants had become young men, what kinds of things did they do?

2As other people joined them how did they expand their activities?

The following questions relate to Parts I – III:

1List phrases which emphasize the villainy of the usurper, Amulius.

2Why does Livy mention more than once that Numitor’s daughter was a Vestal?

3List words that show Livy presenting this story as overseen by the gods.

4How does Livy emphasize the vulnerability of Romulus and Remus by the description of the place where they were exposed? How would this description compare with the Forum in Livy’s Rome?

5Infants exposed at birth were expected to die of starvation or be killed by wild animals. However, the wolf in this story reverses the reader’s expectations. List the words that present the wolf sympathetically.

6In Part II (line 9) fābulae ac mīrāculō is an example of hendiadys: the use of two nouns to describe something where we might expect a noun and adjective. We might translate this as “a wonderful story.” What effect does this literary device have here?

7How does Livy try to ensure that the reader likes Romulus and Remus?

The Tiber today in central Rome.

278 Stage 48

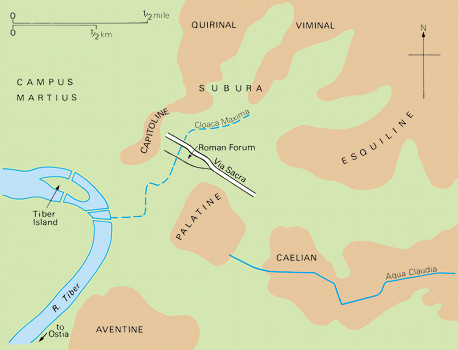

Left: Central and southern Italy.

Below: The city of Rome, with the seven hills marked.

AStudy the following examples:

iuvenēs latrōnēs oppugnāre, praedam dīvidere, iocōs celebrāre.

Young men attacked robbers, divided the plunder, and had fun.

Notice how the infinitive of the verb is used in this sentence, instead of an indicative tense, to describe events happening in the past. This is known as the historical infinitive. It occurs most often in descriptions of lively and rapid action.

BFurther examples:

1omnēs amīcī bibere, cantāre, saltāre.

2in urbe maximus pavor; aliī ad portās fugere; aliī bona sua in plaustra impōnere; aliī uxōrēs līberōsque quaerere; omnēs viae multitūdine complērī. (from Sallust)

Roma or Venus on

the Ara Pacis, Rome.

280 Stage 48

Romulus and Remus eventually restored their grandfather, Numitor, to the throne and killed Amulius. The young men then decided to found their own city.

ita Numitōrī Albānā rē permissā Rōmulum Remumque cupīdō

cēpit in iīs locīs ubi expositī ubique ēdūcātī erant urbis condendae.

et supererat multitūdō Albānōrum Latīnōrumque; ad id pastōrēs

quoque accesserant, quī omnēs facile spem facerent parvam

Albam, parvum Lāvīnium prae eā urbe quae conderētur fore. 5

intervēnit deinde hīs cōgitātiōnibus avitum malum, rēgnī cupīdō,

atque inde foedum certāmen coortum ā satis mītī prīncipiō.

quoniam geminī essent nec aetātis verēcundiā discrīmen facere

posset, ut dī quōrum tūtēlae ea loca essent auguriīs legerent quī

nōmen novae urbi daret, quī conditam imperiō regeret, Palātium 10

Rōmulus, Remus Aventīnum ad inaugurandum capiunt.

| Albānā rē = Albā Longā | |

| permissā: permittere | entrust |

| cupīdō | ambition |

| condendae: condere | found, establish |

| supererat: superesse | be excessive |

| ad id | to this (excess) |

| accesserant: accēdere | be joined, be added to |

| quī omnēs | so that they all (result clause) |

| parvam/parvum | translate as predicate adjectives with fore |

| prae | compared with |

| fore = futūrum esse | |

| intervēnit: intervenīre (+ dat) | interrupt |

| cōgitātiōnibus: cōgitātiō | thought |

| avitum: avitus | of a grandfather |

| rēgnī: rēgnum | rule |

| foedum: foedus | foul, shameful |

| coortum: coorīrī | rise |

| quoniam | since |

| verēcundiā: verēcundia | respect |

| discrīmen: discrīmen | distinction |

| quōrum tūtēlae | under whose protection |

| auguriīs: augurium | augury |

| conditam = urbem conditam | |

| inaugurandum: inaugurāre | take auspices |

1Where did Romulus and Remus want to found their city?

2Why was there a hope that the new city would be larger than both Alba Longa and Lavinium?

3What was the foedum certāmen?

4What problem did Romulus and Remus have in naming the new city?

5With whose help did they resolve this problem?

6Where did each young man go to take the auspices?

Mosaic of wolf and twins.

282 Stage 48

priōrī Remō augurium vēnisse fertur, sex vulturēs; iamque

nūntiātō auguriō cum duplex numerus Rōmulō sē ostendisset,

utrumque rēgem sua multitūdō cōnsalūtāverat: tempore illī

praeceptō, at hī numerō avium rēgnum trahēbantur. inde cum

altercātiōne congressī certāmine īrārum ad caedem vertuntur; ibi 5

in turbā ictus Remus cecidit. vulgātior fāma est lūdibriō frātris

Remum novōs trānsiluisse mūrōs; inde ab īrātō Rōmulō, cum

verbīs quoque increpitāns adiēcisset, “sīc deinde quīcumque alius

trānsiliet moenia mea,” interfectum. ita sōlus potītus imperiō

Rōmulus; condita urbs conditōris nōmine appellāta.10

| fertur | is said |

| duplex | double |

| cōnsalūtāverat: cōnsalūtāre | salute, hail |

| praeceptō: praecipere | receive in advance, take beforehand |

| trahēbantur: trahere | claim |

| altercātiōne: altercātiō | altercation, disagreement |

| congressī: congredī | meet |

| caedem: caedēs | murder |

| ictus: icere | strike |

| vulgātior: vulgātus | common |

| lūdibriō: lūdibrium | mockery |

| trānsiluisse: trānsilīre | jump over |

| increpitāns: increpitāre | speak angrily |

| adiēcisset: adicere | add |

| sīc | supply pereat |

| quīcumque alius | whoever else |

| interfectum = interfectum esse | |

| potītus: potīrī (+ abl) | gain possession of |

| conditōris: conditor | founder |

1Which brother received the first augury? What was the first augury?

2What was the second augury?

3How did the followers of each brother respond to the omens?

4How did the altercation end?

5Outline the vulgātior fāma.

6What did Romulus say?

7What were the two results of Romulus’ action?

The following questions relate to Parts IV–V:

1What do the words sua multitūdō (V, line 3) suggest about the two brothers by this time?

2Give reasons why you think the second version of the death of Remus became vulgātior (V, line 6)?

3Do you think Livy thought one version was more likely than the other? Explain why you think so.

4List the verbs and verb forms associated with Remus in V. What do you notice about them in comparison with those associated with Romulus? Explain what Livy achieves by this word choice.

The following questions relate to Parts I–V:

1To what earlier events in the story do the words avitum malum, rēgnī cupīdō (IV, line 6) refer?

2Etiological myths explain causes or origins. Find three examples in Livy’s story. Where in the story of Daedalus and Icarus did Ovid use etiology?

3Livy presents the foundation and history of Rome as important and as overseen by the gods. In doing this, he provides many details, some of which add color and interest to his tale, while others reveal his skepticism. Find examples of (a) his vivid narration and (b) his skepticism.

4What is there about the story of Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome that has made these stories so memorable? What other myths or legends could be compared with this story?

The Palatine above the Roman Forum.

284 Stage 48

ATranslate each sentence into Latin by selecting correctly from the list of Latin words.

1I gave money to the boy (who was) carrying the books.

| puerī | librōs | portantī | pecūnia | dedī |

| puerō | līberōs | portātī | pecūniam | dederam |

2The same women are here again, master.

| eadem | fēminae | simul | adsunt | dominus |

| eaedem | fēminam | rūrsus | absunt | domine |

3By running, he arrived at the prison more quickly.

| currendō | ad carcerem | celeriter | advēnit |

| currentī | ā carcere | celerius | advēnī |

4If you do not obey the laws, you will be punished.

| sī | lēgibus | pārueritis | pūnīminī |

| nisi | lēgī | pārēbātis | pūniēminī |

5Let us force the chiefs of the barbarians to turn back.

| prīncipēs | barbarīs | revertor | cōgimus |

| prīncipem | barbarōrum | revertī | cōgāmus |

6Men of this kind ought not to be made consuls.

| hominibus | huius | generis | cōnsulem | facere | nonne | dēbet |

| hominēs | huic | generī | cōnsulēs | fierī | nōn | dēbent |

BIn each pair of sentences, translate sentence a; then, with the help of pages 294–295 and 310, express the same idea in a passive form by correctly completing the nouns and verbs in sentence b, and translate again. For example:

atimēbam nē mīlitēs mē caperent.

btimēbam nē ā mīl. . . caper. . . .

Translated and completed, this becomes:

atimēbam nē mīlitēs mē caperent.

I was afraid that the soldiers would catch me.

btimēbam nē ā mīlitibus caperer.

I was afraid that I would be caught by the soldiers.

adīc mihi quārē domina numquam ancillās laudet.

bdīc mihi quārē ancill. . . numquam ā domin. . . laud. . . .

Translated and completed, this becomes:

adīc mihi quārē domina numquam ancillās laudet.

Tell me why the mistress never praises the slave-girls.

bdīc mihi quārē ancillae numquam ā dominā laudentur.

Tell me why the slave-girls are never praised by the mistress.

1adominus cognōscere vult num servī cēnam parent.

bdominus cognōscere vult num cēn. . . ā serv. . . par. . . .

2atantum erat incendium ut flammae aulam dēlērent.

btantum erat incendium ut aul. . . flamm. . . dēlēr. . . .

3abarbarī frūmentum incendērunt ut inopia cibī nōs impedīret.

bbarbarī frūmentum incendērunt ut inop. . . cibī imped. . . .

4ain silvā tibi latendum est nē hostēs tē videant.

bin silvā tibi latendum est nē ab host. . . vid. . . .

5anisi vōs adiūvissem, barbarī vōs circumvēnissent.

bnisi vōs adiūvissem, ā barbar. . . circumven. . . . . . . . .

6anescio quārē prīnceps mē relēgāverit.

bnescio quārē ā prīncip. . . relēg. . . . .

Romulus and Remus on a carving of a shield boss.

286 Stage 48

In his introduction to Ab Urbe Condita Libri, Livy wrote:

quae ante conditam condendamve urbem poeticis magis decora fabulis quam incorruptis rerum gestarum monumentis traduntur, ea nec adfirmare nec refellere in animo.

The things that happened before the city [Rome] was founded or its founding was planned, are handed down more as ornaments for stories from the poets than in the genuine memorials of what was done. These things I do not intend to affirm or refute.

Livy was writing about events seven hundred years before he lived, and he admits from the start that these events are probably more legend than history. So it is perfectly natural that in his writing he includes various versions of the same event. After all, as he says elsewhere in his introduction, history is rērum gestārum memoria: the memory of what has been done. We can record the memory of the past; the actual events of the past are more elusive.

The growth of Rome, from its very humble beginnings to a world power, is an important topic. Reading any history, according to Livy, is a serious occupation, because history provides readers with exempla, patterns of conduct, for individuals and for states, to imitate or avoid. The memory of the Roman past that he records illustrates the changes that growth and prosperity in society bring, until we (the Romans) have reached the point when nec vitia nostra nec remedia patī possumus (we can endure neither our vices nor their remedies).

All through his history, Livy’s focus is on the people who made things happen: in other words, the people who provide the exempla. For example, he tells the story of the three brave Horatii brothers (from Rome) who fought the three Curiatii brothers (from Alba Longa), and the resulting peace between the two towns, broken by the treachery of the Alban leader. The Romans decided to destroy Alba Longa and transfer the people to Rome. The last scene at Alba Longa presents the background noise during the destruction of the town, and, in the foreground, shows the grieving people, looking their last on their homes, everywhere silentium triste ac tacita maestitia (mournful silence and silent sorrow).

Tacitus in his Annals and Agricola, and Suetonius in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars (all of which have served as sources for some of the stories you have read) do the same. It is Tacitus’ picture of the successor of Augustus, Tiberius: cautious, grim, brooding, and resentful, that is still our image of this emperor. In the Agricola, at the same time as he honors his father-in-law, Agricola, soldier and administrator, he presents Domitian: watchful, suspicious, envious. Suetonius, as the title shows, tells the stories of the emperors and their effect on Rome and the empire. None of these historians includes sections on the economic or social conditions of the times. It is the people who create their history.

Livy, Tacitus, and Suetonius consulted a variety of sources. Unlike modern historians, however, ancient historians (both Roman and Greek) did not record those sources in footnotes or bibliographies. They might refer to them in passing, or hint at various versions, but their aim was to produce as dramatic, as serious, as cynical (in the case of Tacitus), as psychologically convincing, in other words as vivid a picture of the event as they could. This might extend to a character in the history giving a speech in which he was quoted as saying the kinds of things that he would have been most likely to say on the occasion being described. A modern historian would find such writing of history scandalous. An ancient historian would not. This is why such histories are works of literature as much as records of the past. In reading them, we savor the style as much as the content. It is a rewarding experience.

288 Stage 48

AMatch the meaning to the English derivative.

1to rateato drive away

2to intervenebto consider, esteem

3to vindicatecto continue to live

4to flexdto clear from criticism

5to repulseeto come between

6to subsistfto mirror an image

7to reflectgto bend

BGive a meaning for each of the following English derivatives of flectere:

1reflector

2deflect

3inflection

4circumflex

5inflexible

6genuflect

CMatch the Latin word to the word opposite in meaning.

1foedusaquia

2quoniambcēlāre

3intervenīrecāmittere

4potīrīdiungere

5quamvīsequamquam

6vulgārefiūcundus

The two sides of a silver denarius showing (left) Caesar and an augur’s

staff, and (right) Juno.

| caedēs, caedis, f. | murder, slaughter |

| flectō, flectere, flexī, flexum | bend, turn |

| foedus, foeda, foedum | foul, horrible |

| interveniō, intervenīre, | |

| intervēnī, interventum | come between, interrupt |

| opīnor, opīnārī, opīnātus sum | believe, suppose |

| pellō, pellere, pepulī, pulsum | drive, strike, move |

| potior, potīrī, potītus sum (+ abl) | obtain, gain possession of |

| quamvīs | although |

| quōniam | since |

| reor, rērī, rātus sum | think |

| seu … seu (sīve … sīve) | whether … or, if … or if |

| subsistō, subsistere, substitī | encounter; halt, stop, stay |

| vindicō, vindicāre, vindicāvī, | |

| vindicātum | protect; avenge |

| vīs, vis, f. | force, violence |

| vulgō, vulgāre, vulgāvī, vulgātum | make known, make common |

numbers

| ūndecim | eleven |

| duodecim | twelve |

| tredecim | thirteen |

| quattuordecim | fourteen |

| quīndecim | fifteen |

| sēdecim | sixteen |

| septendecim | seventeen |

| duodēvīgintī | eighteen |

| ūndēvīgintī | nineteen |

| trecentī | three hundred |

| quadringentī | four hundred |

| quīngentī | five hundred |

| sescentī | six hundred |

| septingentī | seven hundred |

| octingentī | eight hundred |

| nōngentī | nine hundred |

A hut urn.

290 Stage 48